Wit, a 2001 HBO movie starring Emma Thompson, has never really made much of an impression on the viewing public in the

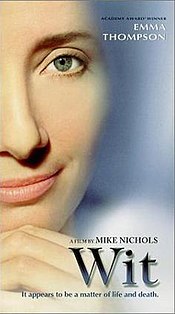

Wit, a 2001 HBO movie starring Emma Thompson, has never really made much of an impression on the viewing public in the To be sure, Wit makes for anything but comfortable viewing. Depicting the suffering of an English Literature professor diagnosed with ovarian cancer, the setting never departs from the hospital, and the plot, if such a word ought to be used, is minimalist. For most of the 99 minutes, all the viewer is presented with is Emma Thompson speaking directly to the camera about seventeenth-century poetry.

Despite this (or, perhaps, because of it), what emerges is an astounding dissection of the human mind under stress. For much of the film I could barely tear my eyes away from the screen, and it was the monologues, not the action, which most inescapably held my gaze.

Many of the reviews of the film I’ve read of the film focus on its truthfulness to life: many reviewers praise the unflinching accuracy of director Mike Nicholls’ work; negative reviewers suggest that the high-minded professor of poetry is nothing like the average cancer sufferer. That, however, might be the point.

What we are presented with is not supposed to be “the average cancer victim”, if such a bizarre concept exists. This is a study of a thoroughly drawn idiosyncratic woman, battling with what ultimately proves to be the death of her.

The progression Professor Bearing undertakes (whether it be typical or not) is from detached and ironic observer to agonisingly implicated victim. On several occasions Bearing shows us scenes from her earlier life, however as the film progresses we come to realise that she is not controlling these reenactments but is trapped within them. One of the most significant moments in the film comes when one such memory (of delivering a lecture) is interrupted by her nurse coming to take her for yet more tests: in Bearing’s mind she is being pulled away from her lecture, in reality she is being forcibly removed from her fantasy. For the first time the ironic mask cracks, and we see for the first time a frightened old woman.

The one jarring factor in Emma Thompson’s outstanding performance is her character’s supposed lack of humanity – she has no family or friends to visit her, while she recalls her insensitive treatment of her students – with her deeply personable tone in her asides to the camera. This, perhaps, is the tragedy of the film: she must confide in the audience because she hasn’t bothered to find herself a friend to listen to her.

In the supporting cast, Audra MacDonald’s Susia comes closest to filling that role, stepping in to block Bearing’s doctors from fully realising their ambitions to use her as a lab rat: Bearing’s treatment is experimental, and as a result she is treated by researchers rather than doctors. Apparently the film is shown in Med Schools to teach aspiring doctors how not to treat patients, but their absence of interest in Bearing as a person (as opposed to a bearer of cancer) seems perversely believable: Jonathan Woodward in particular conveys the awkwardness of a researcher who can find nothing to say to a woman whose life he is watching ebb away.

In the end Susie’s affection (and a last-gasp visit from Bearing’s former professor) provide the humanity that the dying Bearing so desperately needs. Notably these connections are not formed over intellectual conversation, but a (bad) joke and a children’s book. What’s necessary is not intellectual discussion, but human contact.

It has to be said, such a sentence risks reducing the film to trite corniness, it must be stressed that this is far bleaker than a hopeful assertion that love conquers all. Emma Thompson beautifully conveys the exquisite suffering of her character: she is not fighting, she cannot be rescued, she can only marginally alter the manner in which she meets her unwanted end.

As her coping mechanisms fall away and Bearing ultimately dies, suffering the further indignity of having her corpse stripped and displayed to resuscitators she did not want, this dark message paradoxically becomes less hopeless than one might imagine. In the end, as Donne pre-empts, death is inevitable but not meriting of despair. You end the film not simply aware of your own mortality, but powerfully aware of the easily-forgotten fact that you are still alive.

If any of that analysis sounds too clichéd, too cheesy, then perhaps that only bears further tribute to the power of this film: in territory where it is almost impossible not to come across as sentimentally manipulating the emotions of an audience, the stripped-back rawness of Wit transcends cliché. I thoroughly recommend this movie.

No comments:

Post a Comment